How to Reduce All of Arabic Grammar to Just 2 Core Issues That Can Be Summarized in a Sentence Each

I have something very special for you today...

In this blog post that might take you 40 minutes to read, my goal is to give you a bird's eye view of all of Arabic grammar.

Once you're done with this post, there will not be a single rule in Arabic grammar that can ever confuse you, or seem irrelevant to you. You will know exactly why it's important and where it fits in.

Properly internalize what I'm sharing with you here, and your entire study of Arabic grammar will instantly become more enjoyable.

In other words, every new rule you ever come across will actually excite you, and you'll be eagerly anticipating it instead of dreading it.

This is the kind of content that the sister who drove 22 hours from Mississippi was referring to when she said on the al-Maghrib forums many years ago:

Because of that, in one day of class I learned more than an entire _year_ of harvard...

First, let's set the stage and remind you of the core concept:

In the Arabic language the majority of meanings do not come from words. Instead they come from:

1. Vowels

2. Patterns

3. Grammatical Structures

If you take a paragraph of sentences in Arabic and you want to translate it into any other language, you would need at least twice the amount of words, if not more than that.

Because the consonants are giving you separate meaning.

The vowels are giving separate meaning...

On top of that, the way in which the words are arranged together is giving you even more meaning.

So, there are these 3 areas we need to focus on:

meanings achieved from "Patterns"

Patterns is صَرْف.

The Arabic alphabet has 29 letters and they are all consonants.

Meanings are achieved by grouping the consonants into groups of three.

If you were to take the alphabet and group it into groups of three you would have tens of thousands of groups. Every group of three consonants has an associated meaning. But you are not able to pronounce them, because when people speak, they speak in syllables.

Consonants on their own are not pronounceable. So the vowels come to:

1. Remove the limitation and allow the letters to be spoken.

2. Give you more meaning. More specifically the tense and the voice. This is highlighted through the اِسْتَنْصَرُوا example which we covered in a previous article here.

Meanings Achieved From "Vowels"

When we say vowels in this context we mean the vowels at the end of the noun.

الْبَيْــــــتُ vs. الْبَيْــــــتَ vs. الْبَيْــــــتِ

زَيْــــــــــدٌ vs. زَيْــــــــــدًا vs. زَيْــــــــــدٍ

At the end of the اسم [ism] there is a particular vowel that is differentiating between the roles of the اسم. In other languages you might need separate words to do that. In Arabic it is done through vowels. Those are the vowels we are talking about when we say "vowels, patterns and grammatical structures".

I'll explain these last letter vowels that differentiate between the roles of the nouns towards the end of the article, inshallah.

Meanings Achieved Through "Grammatical Structures"

Grammatical structures is obviously the sanctioned methods and the ways in which the nouns can be combined together.

When you take two words and combine them together through one of the methods sanctioned by the language you always end up getting more than what you started off with. Those are phrases. (More on this later)

Topic of This Blog Post: Sentences

When we speak about sentences, the first thing is: what is the definition of the sentence?

Here is a very brief definition:

when you take two or more words and connect them together in a manner that conveys to the listener a complete benefit upon which silence is appropriate.

In other words, once you’re done speaking your two or more words, and you become quiet, one of two things will happen. Either:

1. Your listener will be satisfied, and they will have received a complete benefit and they are not waiting for anything further.

2. They are still waiting, and they want you to finish it.

If they are not waiting that means you are done with the sentence, you can put a period and you are done. If they are still waiting, then that means what you spoke is a phrase.

Two Parts of the Sentence

Every sentence has 2 parts.

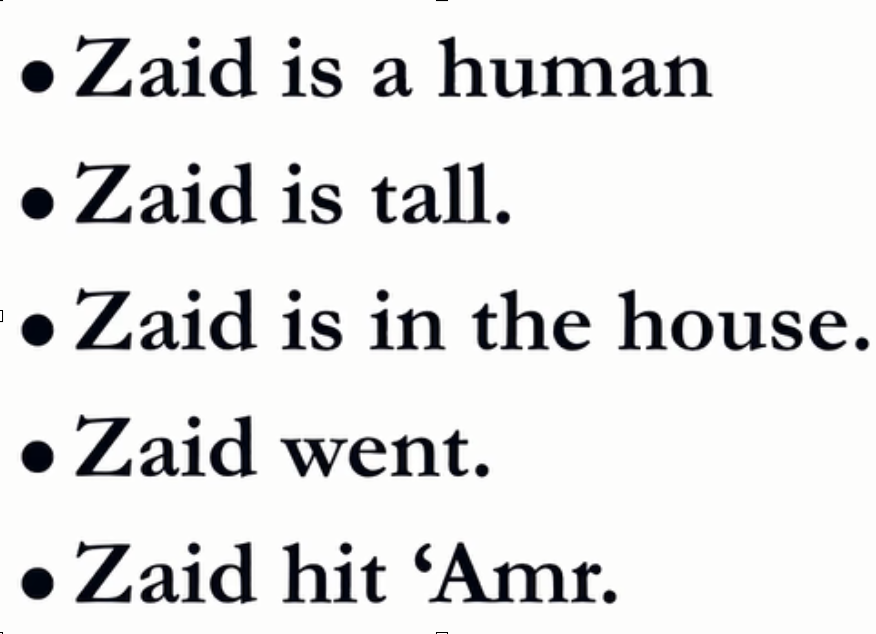

1. There is the primary portion which we called the subject. This is the thing you are talking about which has to be a noun or entity. Like the word “Zaid”. I can create multiple examples: Zaid is a human. Zaid is tall. Zaid is in the house.

Zaid would be the subject of the sentence. Regardless of the kind of predicate, the subject will always be a noun.

2. The predicate, which can be another noun, or it can be an adjective, a compound structure, a verb, a verb plus an object.

5 Examples

Here are five examples. If you remember these five examples you will never forget this topic.

What is common between all 5 examples?

The word “Zaid” is at the front. We can say that regardless of the kind of predicate you are dealing with in English grammar the noun will always be at the front.

In the first example “Zaid is a human”, the predicate is another noun.

In the second example “Zaid is tall”, the predicate is an adjective.

In the third example “Zaid is in the house” the predicate is a compound structure.

In the fourth example “Zaid went”, the predicate is a verb.

In the fifth example “Zaid hit Amr”, the predicate is a verb plus an object. So it is like a two word predicate.

Regardless of the kind of predicate you use, in English “Zaid” will always be at the front.

But in Arabic grammar in three of them “Zaid” would be at the front, but in two of them the verb would be at the front and “Zaid” would get pushed forward.

You don’t have to use a verb in all the examples. In the top three examples there is no verb. In the fourth and fifth examples there are verbs. The minute you choose to use a verb, the verb will be at the front. It is a rule. In Arabic grammar the subject of verbs must follow the verb.

Here are the five examples again, this time in Arabic:

زَيْدٌ إِنْسَانٌ [Zaid is a human.]

زَيْدٌ طَوِيلٌ [Zaid is tall.]

زَيْدٌ فِي الْبَيْتِ [Zaid is in the house.]

ذَهَبَ زَيْدٌ [Zaid went.]

ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا [Zaid hit Amr.]

What you are seeing is that regardless of the kind of predicate you use in English, the subject is always at the front. In Arabic 60% of the time the subject is at the front, 40% the subject gets pushed forward and the verb is at the front.

Is this significant? The answer is it is very significant.

The grammar people noticed this. Based on this they said this change is so fundamental that let’s go ahead and assign it a classification.

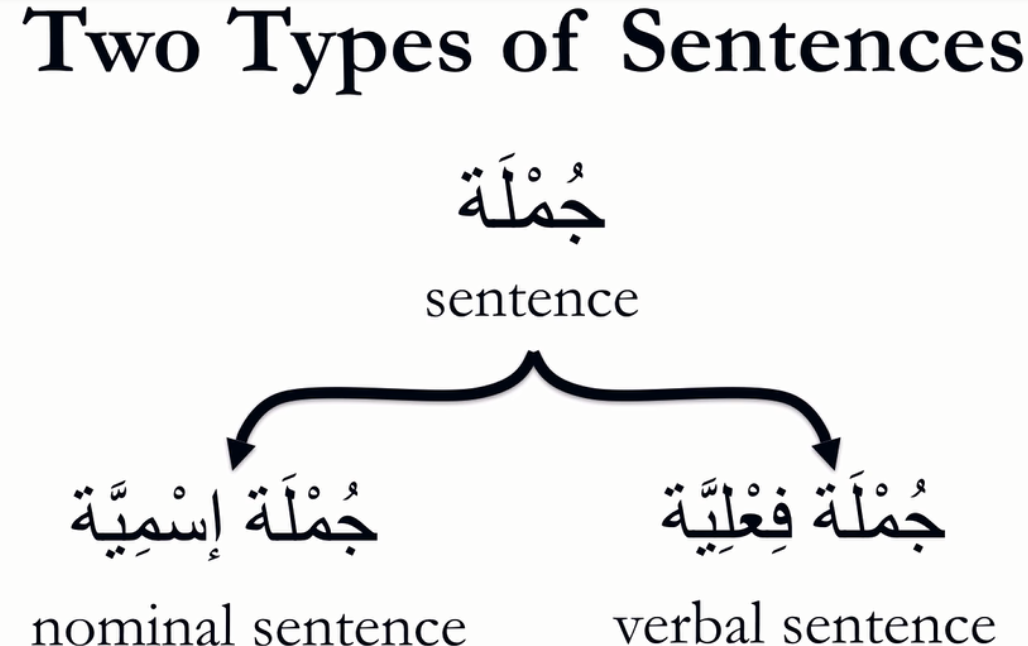

So, they took the sentence and divided the sentence into two types:

They said:

Sentences that begin with an اسْم [ism], we are going to call them جُمْلَة إِسْمِيَّة.

Sentences that begin with a verb, we are going to call them جُمْلَة فِعْلِيَّة.

In those five examples, the top three are examples of جُـمْلَة إِسْمِيَّة, and the bottom two examples are of جُمْلَة فِعْلِيَّة.

The top three we can say are sentences without verbs.

(Technically the word “is” is a verb, but it is not represented in Arabic. زَيْدٌ إِنْسَانٌ and زَيْدٌ طَوِيلٌ only have two words. I can say the top three examples are verbless and that would be accurate enough for our purposes. In this context I mean verbs like hitting, helping, sitting, standing, eating and drinking. The top three examples do not have a verb of that kind).

It is about whether the verb is there of whether it is not there. If it is not there, then it is a جُـمْلَة إِسْمِيَّة, and if that kind of verb is being used then automatically it causes a rearrangement in the words, and the predicate now is preceding and the doer of the verb is delayed. Since this happens in Arabic and doesn’t happen in English, that is why the number of terms you need to retain in English grammar are just two: subject + predicate.

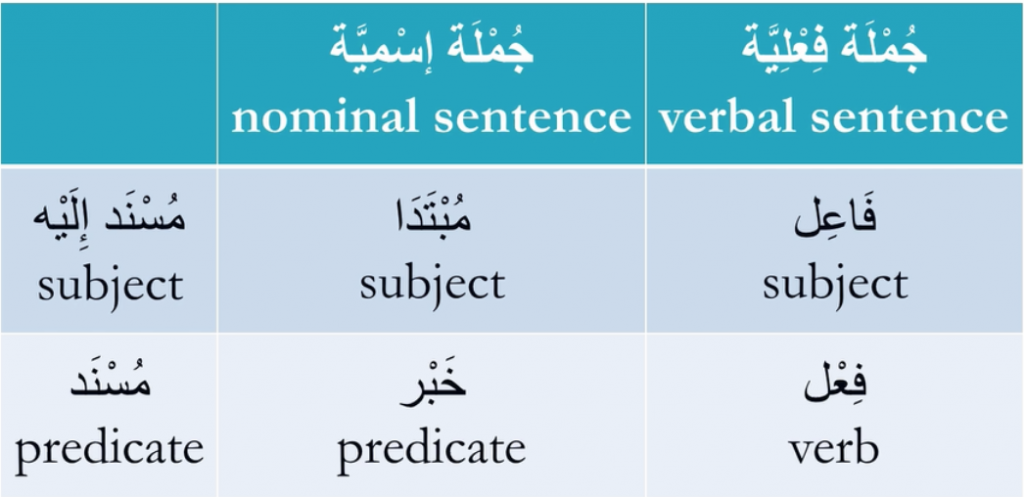

In Arabic grammar, since there is this fundamental shift occurring, that in certain sentences the subject is at the front and in other sentences the subject is pushed forward, the Grammar people have six terms. There are two terms that are generic (subject and predicate), and there are four more specific terms. These are represented below:

In the far left we have مُسْنَد إلَيه and مُسْنَد, that is regardless of the kind of sentence you are dealing with. Every sentence has a مُسْنَد إلَيه and مُسْنَد .

When you go more specific and they ask you the question, that زَيْدٌ إِنْسَانٌ. What are those? You can say زَيْدٌ is مُسْنَد إِاَيْه and إِنْسَانٌ is مُسْنَد, that would be valid. But it is like referring to wine as a liquid. There is no need to do that, because we have a better word, and that is beverage.

The difference between مُبْتَدَأ and مُسْنَد إلَيه is the difference between beverage and liquid. مُبْتَدَأ is more specific and مُسْنَد إلَيه is more generic.

Do we totally discard مُسْنَد إلَيه and مُسْنَد? No, they are useful as well. Like in balagha, when the ideas are conceptually in your head, they are called مُسْنَد إلَيه and مُسْنَد. Then you look for words to communicate the ideas in your mind. Now, when you say it, the format you use would dictate the terms that will be applied. When they were in your mind they were مُسْنَدإلَيه and مُسْنَد. Then when they appear in the language, in an actual sentence, you would use the more specific terms:

- In the case of the جُـمْلَة إِسْمِيَّة [nominal sentence] you would use: مُبْتَدَأ andخَبْر.

- And in the case of جُمْلَة فِعْلِيَّة[verbal sentence] you would use: فِعْل and فاعِل.

Let’s continue now with further examples. We already have five examples, which are somewhat sufficient to understand this topic.

Nominal Sentence

If you want to go with the basic examples for the جُـمْلَة إِسْمِيَّة [nominal sentence] we have:

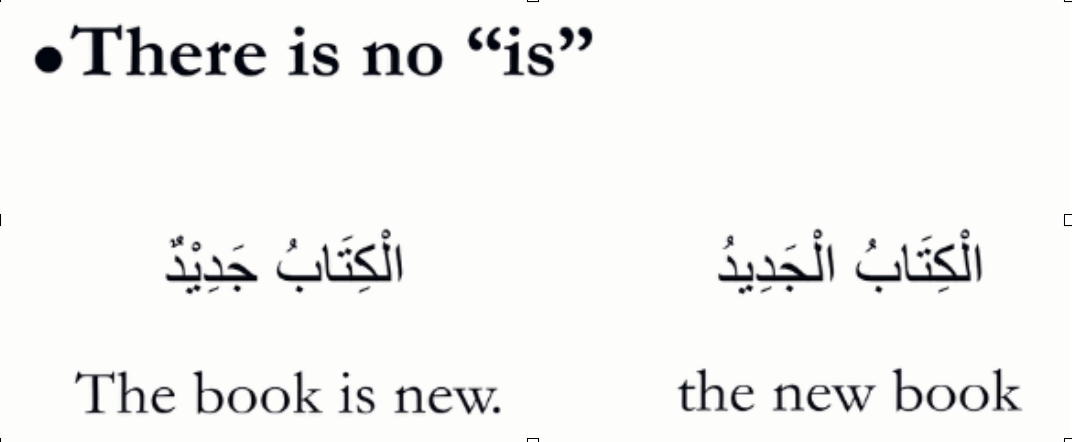

الْكِتابُ جَدِيدٌ [The book is new.]

This is an example of a sentence that doesn’t have a verb. By this I mean verbs like hitting, helping, sitting, standing, eating and drinking. The word “is” is automatic. There is no word that represents “is”, but you would still have to differentiate with the phrase, since you don’t want it confusing with “the new book”. We will talk about this in a few minutes. [see “Issue in the Nominal Sentence” below]

الْكِتابُ جَدِيدٌ when you compare it with the five examples above, which example does it align with the best? The correct answer is, it lines up best with the second one: زَيْدٌ طَوِيلٌ [Zaid is tall.] Both جَدِيدٌ [new] and طَوِيلٌ [tall] are adjectives.

Verbal Sentence

An example of a basic جُمْلَة فِعْلِيَّة [verbal sentence], keeping in mind the fact that the doer of the verb must follow the verb, would be:

ذَهَبَ زَيْدٌ [Zaid went.]

This is identical to the fourth example given earlier.

If a verbal sentence is just two words, it is not a big deal. The translation cannot mean anything else. It can only be “Zaid went”.

But if the sentence is larger and longer, then now it becomes an issue of how do you differentiate between the roles of an اِسْم? You would have to be able to slot those isms [اِسْم] into their proper slots. For that let’s revisit the Parts of Speech.

Parts of Speech

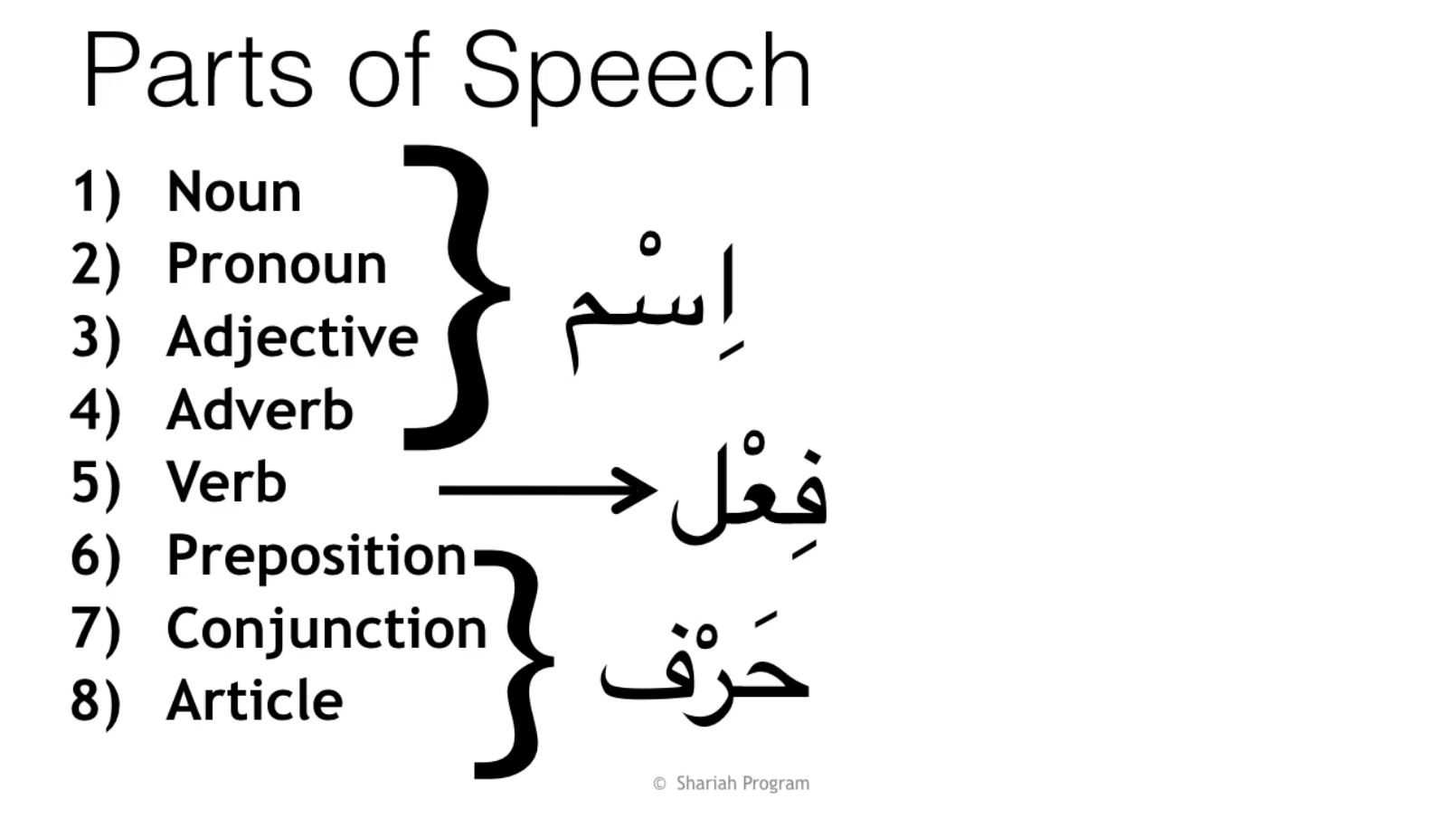

The parts of speech in Arabic are just 3, in English there are more. We covered this in depth here.

Recall that اِسْم [ism] in Arabic is not just noun. It is also serving all the purposes pronouns, adjectives and adverbs would serve.

In the example “Today I came quickly”, there is the verb “came”, “I”, “today”, and “quickly”. In English grammar that would be verb + a pronoun + 2 adverbs. But in Arabic grammar we would simplify it. We would say a verb followed by 3 isms [اِسْم].

The point is that the verbal sentence can become longer. The bare minimum for a verbal sentence along with the verb is at least one noun. That noun can be physically present, or it can be carried within the verb.

Example: ذَهَبَ with nothing after it, is 2 words. ذَهَبَ زَيْدٌ is 2 words also.

You cannot have a sentence with less than 2 words.

For the maximum there is no limit. The verbal sentence can be longer and what dictates the length of the verbal sentence is the amount of details the speaker chooses to disclose. The sentence will have a when, where, why, how. If it is relevant and important and the speaker feels the need to communicate that, they would need to add additional isms to the sentence in order to communicate those details.

It is quite normal for a verbal sentence to be followed by 3 to 5 isms.

Issue in the Verbal Sentence

Here is an example: ضَرَبْتُ الْيَوْمَ عَمْرًا [Today I hit Amr.]

This is an example of a verb followed by 3 isms:

1. تُ

2. الْيَوْم

3. عَمْرًا

In English that would be a verb + pronoun + adverb + noun.

In Arabic, we don’t make that distinction. Therefore, we say a verb followed by 3 isms.

Here is another example: ضَرَبَ الْيَوْمَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا [Today Zaid hit Amr.]

In English, that would be a verb + adverb + 2 nouns. (The word "today" is considered an adverb as it answers the question "when").

In Arabic, again it would be a verb followed by 3 isms.

When the verbal sentence is only 2 words, then there is no issue. ذَهَبَ زَيْدٌ can only mean “Zaid went”. It cannot mean anything else.

The minute it becomes longer, it becomes an issue. Which of the 2 nouns is the one doing the verb, and which of the two nouns is the one upon whom the verb is being done.

If there are adverbs being used, then the reader and listener needs to know what those adverbs are doing. i.e. which questions are they answering.

If there is a verb followed by 5 isms. One of those 5 isms is:

1. the one doing the verb,

2. the one upon whom the verb is being done,

3. the answer to the question when,

4. the answer to the question how.

5. the answer to some other question the speaker is trying to disclose

You need to be able to read the sentence and be able to effortlessly slot those isms into their proper roles. You have to do it without wasting mental energy. Because the assumption is you are lying on your bed and have the Tafsir of Ibn Jarir in your hands. You are reading what the scholar is writing. If you are pausing on every verbal sentence and you are spending five minutes figuring out which noun is the doer, which noun is the object, and which is the when, the why and the how, then you are going to gas out before you get through a single paragraph.

How do you facilitate speed reading? And how do you go through pages of material without feeling overwhelmed? You have to be able to slot the isms into their proper roles. This becomes particularly significant and important given the fact that sequence does not determine grammar.

Some languages use sequence to do it. Some languages use extra words.

Arabic does not have extra words to help you with this. It also does not use sequence.

In Urdu for example, they say “Zaid ne Amr ko mara” [Zaid hit Amr]. The extra words “ne” and “ko” are differentiating between the roles of the اِسْم and it becomes a non-issue.

In English the order of the words is determining the grammar. Again, it is a non-issue.

Solution: Grammatical States Process

In Arabic, since sequence does not determine grammar, and we don’t have extra words, the question is: How do we determine the grammar?

We do it through a particular process. This is the process that is likened to human emotions and facial expressions. We call it the Grammatical States Process.

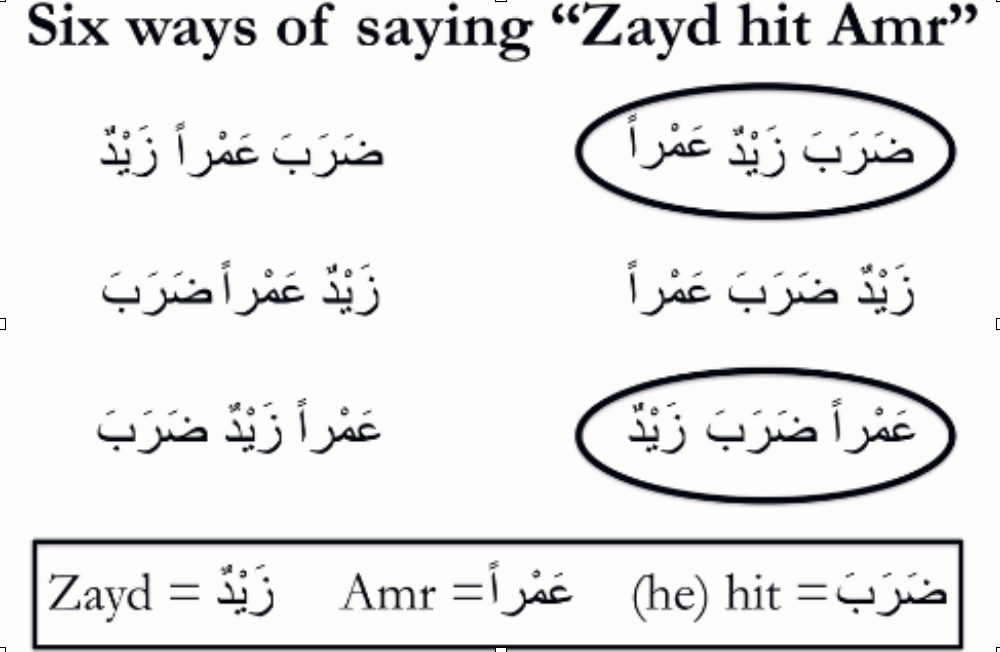

Let me give you an example with 6 ways of saying “Zaid hit Amr”.

One of them is the default one. If you wanted to communicate that “Zaid hit Amr”, you wouldn’t deviate away from ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا.

The other five are available and are all valid, and they mean the same thing. They are all available for you to create a better match with the audience. The listener might already know that the hitting happened, and it was Zaid that did the hitting. The only new information you are communicating is that it was Amr that Zaid hit. You would use the one with عَمْرًا at the beginning. (The one circled in the bottom right corner). That is the benefit of this.

It gives you flexibility. You can arrange the verb and two nouns in multiple ways, and create a better match with the requirement of the occasion.

How do we differentiate between the roles? زَيْدٌ in all six examples is زَيْدٌ, and عَمْرًا in all six examples is عَمْرًا. The particular ending that زَيْدٌ has is telling us that “Zaid” is the subject and the particular ending that عَمْرًا has is telling us that Amr is the object. Now it doesn’t matter whether “Zaid” is at the beginning, middle or end. The meaning is the same.

The problem within verbal sentences is that sequence does not determine grammar. The solution is to know:

* the grammatical states,

* and how they are reflected at the end of the اِسْم.

Issue in the Nominal Sentence

In the case of a nominal sentence it is a different issue. Again, when the nominal sentence is just two words it is a non-issue. (Just like when the verbal sentence was just 2 words, it was a non-issue).

الْكِتابُ جَدِيدٌ can not mean anything else. Of course we have to still be able to keep it separate from the phrase: الْكِتابُ الْجَدِيدُ . You don’t want to mix it up with the phrase. And to be able to not mix it up is merely a function of knowing the requirements of the phrase, that in the مَوْصُوف-صِفَة, [the noun-adjective phrase], both parts of the phrase need to match in their definite and indefinite value.

When you know that, and you are faced with الْكِتابُ جَدِيدٌ, you have no trouble disqualifying the phrase.

Because الْكِتابُ جَدِيدٌ are not matching. الْكِتابُ is definite and جَدِيدٌ is indefinite.

With that out of the way, there is no issue. Now, even though there is no “is”, you would translate it as “The book is new.”

But when the nominal sentence becomes larger, 3,4,5 words, and the fact we don’t have an “is”, you have to be able to divide the sentence into its proper parts. You would have to determine from where to where is the مُبْتَدَأ and from where to where is the خَبْر.

In English determining what the subject and predicate is, is a non-issue. I can give you a very long sentence and you would have no trouble figuring out the meaning of it. E.g. “This masjid which Ishaq (peace be upon him) built in Shaam is Baytul Maqdis”.

Did you have any trouble with that? It was 10+ words but still you had no trouble with it. Because there is a word in English, that what is on its left side is the subject, and what is on its right side is the predicate. That word is “is”. Here is how it would be in Arabic:

هذَا الْمَسْجِدُ الَّذِى بَناهُ إِسْحاقُ فِى الشَّامِ بَيْتُ الْمَقْدِسِ

From هذَا until الشَّامِ is the مُبْتَدَأ. And بَيْتُ الْمَقْدِس is the خَبْر.

But the Arabic does not have an “is”, how do we figure this out? Conceivably it could have been هذَا on its own being the subject, and الْمَسْجِدُ onwards connecting and forming the predicate. Or it could have been هذَا الْمَسْجِدُ forming the subject and الَّذِى onwards connecting and forming the predicate. How do we know this?

Remember, the earlier issue in the verbal sentence was that the verb was followed by multiple isms . We needed to be able to slot those isms into their proper roles without wasting mental energy. Especially given the fact that sequence does not determine grammar and we don’t have extra words. It is done by knowing the process that is likened to human emotions and facial expressions.

In our premium program, that is taught in week 3. A little of it I will teach right now as well. Just keep reading.

Solution: Knowing 16 Types of Phrases

In the nominal sentence the issue is a completely different issue. It is the lack of “is” issue. To be able to determine from where to where is the مُبْتَدَأ and from where to where is the خَبْر. We do it by moving from right to left, and looking for phrase level relationships. At some point we will notice that the phrase level relationships stop, and there are no requirements being satisfied. When that happens you know your مُبْتَدَأ is over and that is where the خَبْر begins.

In the above example, we look at the phrase level relationships. The types of phrases in Arabic are 16. The possessive phrase is one of them, the descriptive phrase is another. The requirements for a possessive phrase are:

1. Noun “a” needs to be empty of ال [al] and be empty of tanween.

2. Noun “b” needs to be in the state of جَرّ [jarr]. Have a very specific ending. E.g. كِتَابُ زَيْدٍ.

If you start your sentence with a noun that is empty of ال [al] and also doesn’t have tanween, and the second word is in the sentence is in جَرّ then you cannot drop the “is” in between and say كِتَابُ is مُبْتَدَأ and زَيْدٍ is the خَبْر [predicate], because the two are functioning as a single unit. As long as the requirements of a particular phrase are being satisfied, the predicate cannot begin. It has to happen after all of this is done.

Pay a little more attention to this example. The word هذَا means “this”. I know this from my knowledge of Arabic grammar. You will also learn this at some point. This is an ongoing process. The point is not to learn all of grammar in one hour. I am highlighting the issue and I am telling you what the solution is. You are not going to be able to apply this solution yourself until you know the 16 phrases.

هذَا , can occur on its own or it can occur coupled with the upcoming noun as part of a phrase.

What determines whether هذَا is on its own vs. whether هذَا is combining with the upcoming noun and forming a phrase, is the upcoming noun:

having an ال [al] or

not having an ال [al].

The question is does the upcoming noun have an ال [al]? The answer is yes it does.

What I wouldn’t do is say هذَا is مُبْتَدَأ and الْمَسْجِد onwards is خَبْر. That is not allowed. الْمَسْجِدُ and هذَا together are forming a phrase. I would do the same thing that I did between هذَا and الْمَسْجِد , with الْمَسْجِد and الَّذِى. I will look for a phrase level relationship. I know this based on my knowledge of the Arabic grammar, which YOU WILL EVENTUALLY LEARN ALSO…

[It is like the اِسْتَنْصَرُوا example that was covered in this article. I teach that right at the beginning, to people who don’t know what passive is, what enhancements are, and that س [seen] and ت [taa] is for “seeking”, and ن [nun] ص [saad] ر [raa] are for “helping”. The point is this is an EXAMPLE. Please don’t overthink this. The individual topics I'm leveraging within this example are supposed to be taught more appropriate time.]

[Continuing from above] …Very briefly, whenever you have a noun and you want to describe it using an adjective as part of a phrase, you need to make sure the noun and the adjective are matching. It would be:

- الْكِتابُ الْجَدِيدُ [the new book] and

- كِتابٌ جَدِيدٌ [a new book]

How about If you want to describe a noun using a full sentence while keeping the whole thing a phrase? [Back to the هذا الْمَسْجِد example] “The masjid” is being described by the fact that “Ishaq built it in Sham”, which is a full sentence. When you do that in English, you use “who”, “what”, “which”. The “who”, “what”, “which” needs to come in between, and you would say “This masjid which Ishaq built in Sham is Baytul Maqdis” In Arabic the equivalent for that is الَّذِى.

We have a phrase level relationship going on between:

الْمَسْجِد and the entire الَّذِى بَناهُ إِسْحاقُ فِى الشَّامِ structure.

الَّذِى بَناهُ إِسْحاقُ فِى الشَّامِ is being introduced with the relative pronoun الَّذِى.

Relative pronouns presuppose clauses. You cannot have “who”, “what”, “which” and not be followed with a sentence after that. You cannot say “this is the book which”, and just end it there. Or “I read what” and just end it there. You have to say, “I read what you wrote”. The “you wrote” is called the clause. We have the relative pronoun plus the clause. The two together connect and form whatever they are going to form. They function as a single unit. الَّذِى plus بَناهُ إِسْحاقُ فِى الشَّامِ is one of the 16 phrases, in case you haven’t already figured it out!

I know the requirements of it so I can do it effortlessly. I don’t have to spend any time on it. The point is as a student these are the things you will be taught, and it is incredibly liberating to know these things ahead of time.

A lot of people study for ten years, nobody shows them the relevance of phrases. They don’t know why phrases are important or what role they play. In this blog post I am highlighting the most important topics in Arabic grammar and I am telling you, here is the relevance of it. This is huge and incredibly valuable. Hopefully you are appreciating it!

Now that الَّذِى is there, the predicate cannot start! بَناهُ is a clause and the clause is a full sentence. The sentence has to complete. Unless that sentence completes the predicate cannot start. إِسْحاقُ is the فاعِل for بَناهُ and فِى الشَّامِ is connected to the verb. Now we hit the الشَّامِ, we see is anything missing. Have all of the requirements of the الَّذِى structure been satisfied? The answer is yes.

Now the word بَيْتُ is coming.

Does it connect in any way, shape or form? The answer is no. We drop the “is” in between. From هذا until الشَّامِ, all of those words connect and form the مُبْتَدَأ and بَيْتُ الْمَقْدِسِ connect and form the خَبْر .

The total number of words are 10, and the division is 8 and 2. I can say that with 100% confidence. When you know all the principles that led to that, your confidence will also be 100%. The point is that it becomes subconscious. When you are reading you just drop the “is” in the correct spot.

Recap

To recap, the problem in the nominal sentence is the lack of “is”. How do you know from where to where is the مُبْتَدَأ and from where to where is theخَبْر?

The solution is be able to know the phrase level relationships, and be able to move from right to left and exhaust them. Then drop the “is” where the phrase level relationships end.

Phrases are important, because without knowing phrases you cannot translate them. If I give you a ten word long nominal sentence and I tell you to translate it, your likelihood of translating it correctly is really low. Unless you know the 16 phrases. Again the 16 phrases are not created equal. There are 3 or 4 that are more important than the other 12 combined. مُضاف-مُضاف إلَيه and مَوْصُوف-صِفَة definitely belong to the important ones.

If you know the vocabulary of every word in the ten word long nominal sentence and you know the requirements for the phrases, it is logically impossible for you to mistranslate that sentence.

That is how important this is. If you do not know the phrases, then your likelihood of mistranslating is incredibly high. So knowing the phrases is key and is essentially half of grammar.

Grammatical States

The other half of grammar is Grammatical States.

Grammatical states is important because the اِسْم can be used in different ways, When a verb is combined with multiple isms, differentiating between the roles of the nouns becomes important.

Introduction to Grammatical States - Human Emotions and Facial Expressions Analogy

We say human beings experience emotional states, people make us happy, sad, angry, embarrassed, frustrated.

Sometimes they satisfy our expectations, other times they don’t. It happens because of interaction with other humans. These emotions are then reflected on our faces.

By looking at a person’s face you can tell what state they are experiencing.

Arabic words behave in a similar fashion. Words interact with other words. They induce change and cause the upcoming words to enter grammatical states. These states are then reflected on the last letter.

Unlike human emotions which are endless, grammatical states in Arabic (for the اِسْم) are just 3.

Second Analogy - English Pronouns

We see this to a very limited degree in English pronouns. When I say “we see this” I mean the word looking different based on how it is used. We have a meaning and we are trying to communicate that meaning in three different sentences. The word will look slightly different in all three. For most pronouns, you have three versions: he, him and his. When the pronoun is intended to be:

1. Subject of verb, you would say “he came”

2. Object of the verb – “I saw him”

3. Part of a possessive structure – “his pen”

Why do they have 3 versions? The reason is you have to pick the correct one. You wouldn’t do that in nouns. If it is a noun occurring in multiple ways, the noun looks the same. Why? Because sequence is determining grammar. There is no need to change the word. Just to give you a little idea we presented the English pronouns.

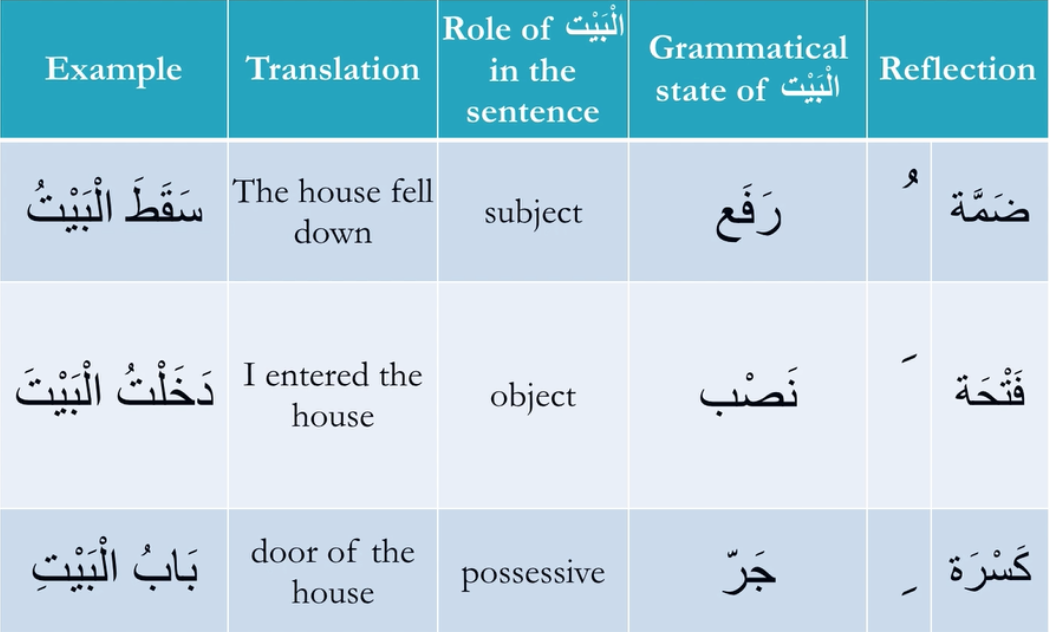

The states the اِسْم experiences are 3:

رَفْع [rafa’]

نَصْب [nasb]

جَرّ [jarr]

If you wanted you can write beside رَفْع “he”, besides نَصْب “him” and besides جَرّ “his”. So in English, the pronoun would change but the noun would not.

If you look in the “Translation” column, it is “house” in each one.

But if you look in the “Example” column, the Arabic word الْبَيْت is different. Does رَفْع mean subject? Does نَصْب mean object? Does جَرّ mean possessive? You can think of it like that. But really these are just examples. Because the اِسْم is not restricted to being used in just 3 ways. Subject, object and possessive are examples to get our foot in the door.

If you want to be more accurate you would have to contemplate the total number of ways an اِسْم can be used. That number is a large number: 22.

Why is the number so large? Because the اِسْم is very broad and it has a lot to do. It has to serve all of the purposes an adjective would serve. It has to serve all the purposes an adverb would serve. And also the “when”, the “where”, the “why” and the “how”.

If I have a verb followed by 5 isms, that would be 5 examples of the way an اِسْم can be used. One of them is subject, the other is object, the other would be the answer to the questions “why”, “how”, “where” and “when”. Then we have different kinds of sentence. We have nominal sentences ,verbal sentences , كانَ version sentences (sentences that begin with kaana), إِنَّ version sentences (sentences that begin with inna).

The specific components for every sentence are labelled differently.

In a nominal sentence, the parts are called مُبْتَدَأ and خَبْر.

In a verbal sentence, the parts are called فِعْل and فاعِل. If there is an object then that object is called مَفْعُول بِهِ. The “when”, “where”, “why” and “how” all have different names. These are all examples of ways in which an اِسْم can be used.

The “house” example doesn’t really do justice. The “house” example sort of projects the اِسْم can be used in 3 ways. But that cannot be true.

The total number of ways an اِسْم can be used is actually 22. Yet there are only 3 states.

Here is the million dollar question.

If the اِسْم can be used in 22 different ways, why don’t we have 22 different endings and 22 different states?

For example, فاعل having its own ending, مفعول به having its own ending, مبتدأ having its own ending, خبر having its own ending, subject of a كان sentence having its own ending, the predicate of a كان sentence having its own ending and so on and so forth....

The answer is because there is no need for that.

We don’t need that many endings. First of all, we don’t have that many endings. We just have 3 vowels. We are not going to invent 19 more vowels. Vowels are somewhat limited to start with. The other reason is that it would be redundant. I say this because many of the 22 places do not line up side by side.

Examples:

ذَهَبَ زَيْدٌ [Zaid went]

زَيْدٌ إِنْسَانٌ [Zaid is a human].

The vowels I used on زَيْدٌ in the first example are the same as the vowels I used on زَيْدٌ in the second example.But that is not problematic because you are not going to encounter the فاعل and the مبتدأ side by side. It allows me to recycle the vowel and use it more than once. زَيْدٌ and إِنْسَانٌ having the same ending is not a problem either. Why not? Because it is not about differentiating between roles anyway. It is about knowing where to drop the “is”. The solution to that is to know the phrases. (Different solution altogether).

In هذَا الْمَسْجِدُ الَّذِى بَناهُ إِسْحاقُ فِى الشَّامِ بَيْتُ الْمَقْدِسِ example الْمَسْجِدُُ and بَيْتُ both were ending in dhamma, but it is not a problem. It did not stop us or get in our way in understanding the meaning of that sentence. Actually it played no role whatsoever.

The point is that if a verb is followed by 2 isms. Then if those 2 isms have the same ending, that would be an issue. Because truly we would not know which of the 2 nouns is the one doing the verb and which of the 2 nouns is the one upon whom the verb is being done. Because they are both candidates. “Zaid” could conceivably be the doer and “Zaid” could conceivably be the object. “Amr” could conceivably be the doer and “Amr” could conceivably be the object. So we need them to be different. But the مبتدأ and فاعل do not need to be different. The مبتدأ and خبر do not need to be different. [Re-read for further clarity!].

Sometimes the kind of word gives it away.

The best example I can give you of this is: ضَرَبْتُ الْيَوْمَ عَمْرًا[Today, I hit Amr.] The word الْيَوْمَ and عَمْرًا have the same ending, yet there is no problem determining the meaning of the sentence. الْيَوْمَ is a time, and عَمْرًا is an entity. You cannot “hit” the time, and the entity cannot be the answer to the question “when”. So, the meaning of the sentence is clear, yet they have the same ending.

What we don’t need is 22 different endings. What we do need is the bare minimum amount of endings that would remove all confusion, and that number happens to be 3.

You are not going to hear this anywhere else!

What do we do now?

We study and understand the 3 grammatical states, not as subject, object and possessive, because رفْع does not mean “subject”, نصْب does not mean “object” and جرّ does not mean “possessive”....

..but rather we understand them thoroughly, with a deep understanding, and we understand them as broad categories. The 3 states the اسْم experiences are broad categories, and the 22 possible ways are distributed among the 3 categories.

What is the division? It is 8 - 12 - 2.

There are 8 possible ways an اسْم is used in the language, that are all رفْع based.

There are 12 ways that are نصْب based.

There are 2 way that are جرّ based.

If you know that, you know half of grammar!

The other half is phrases.

You Can Definitely Do This!

It should feel like a 20lb weight has been lifted off your shoulders right now. This is so manageable. There is no reason why you cannot be a master and expert in grammar, and to be able teach at my level with just a few months of effort.

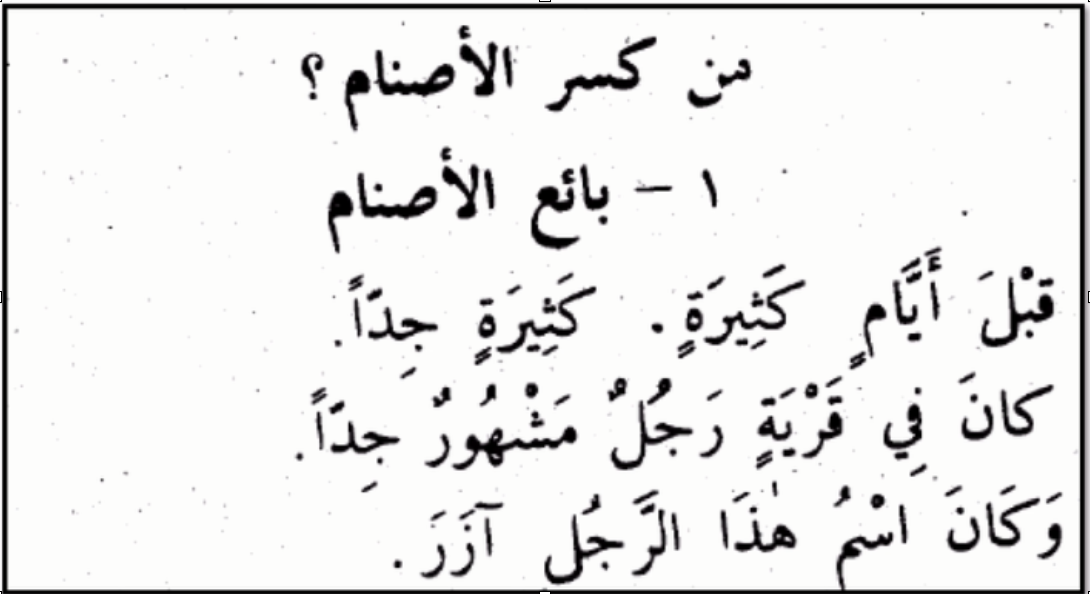

This is what we mean when we say you start reading an Arabic book in 21 days, or you start understanding Qur’anic Arabic by the third week of class. I mean you cannot understand the entire language in 21 days. But the point is most people can be studying for 10 years, but they cannot even access a basic children’s book, like this:

Arabic is the first thing the scholars study, and they continue studying it for the rest of their lives.

The studying is not going to finish in 21 days. But you will get out of the beginner stage and you are going to be able to access your first Arabic book within 21 days. That is incredibly liberating!

It means you are no longer spinning your wheels. Now all the considerable effort is over, and it becomes enjoyable. Now you are getting the pay off, and everything is coming to life.

When we go through the above passage in the book, we are going to ask questions. We don’t speak about everything. We speak about what we can use to enhance the understanding we have achieved thus far. Then we teach new grammar gradually in a way that does not overwhelm the students.

We are now done with this blog post. I would like to remind you, this is what makes the Qur’an miraculous. When you understand the meanings that are coming from other than the words. And when you understand and appreciate that words can be combined together in many different ways. Just with a verb and 2 nouns, it can be formatted in 6 different ways. If you add to that an adverb, the number jumps to 24. When you add to that a prepositional phrase the number jumps to 120. It becomes a staggering amount of ways that meanings can be communicated.

When the Qur’an uses the most precise and most appropriate structure, each and every time, this is what gets noticed and this is what dumfounded the pre-Islamic Arab. This is what Allah (swt) meant when He said:

أَفَمَن كَانَ عَلَي بَيّنَةٍ مِنْ رَبّهِ وَيَتْلُوهُ شَاهِدٌ مِنْهُ

Can the rejector of the Qur’an ever be equal to the one who is upon evidence from his Lord? And to it is attached its own internal witness. (Hud, Verse 17)

That means there is something built within the Qur’an that testifies that it is the Word of Allah. There is external testimony also and that is in the form of the previous scriptures. The verse continues:

وَمِن قَبْلِهِ كِتَابُ مُوسَي إِمَاماً وَرَحْمَةً

And prior to it was the Book of Musa which was a guide and a mercy (for the world).

But that is not all. There is also a miracle built into the Qur’an. That is the special use of the language within the Qur’an. When you know the dynamics of how the language works, and you can appreciate the nuances of when an object is brought forward before the verb, and when the structures are re arranged. Then this is how you appreciate the miracle of the Qur’an.

If you want to understand more and more of the messages Allah (swt) has intended for you, and if this method appeals to you and if you have gained a lot from this single blog post, then just imagine how far you can go, if you formally register for the premium program.

I would strongly encourage you to click on this link here and get on the early bird list. If you liked the video, then you are really going to love our Premium Program. Registration opens in just a few days and the amount of seats are very limited. As you know, there are thousands of people visiting these articles and watching the videos and other things we share to our mailing list subscribers.

But if you get on the early bird list, then when we officially open up registration in just a few days you will guarantee yourself a spot. If you are not ready for that then that is ok. The program is serious and does involve considerable commitment. We want you to join when you feel ready, inshallah.

Please like and share this using the buttons below.

That said I look forward to speaking with you soon.